Testing Smarter with Mike Bland

This interview with Mike Bland is part of our series of “Testing Smarter with…” interviews. Our goal with these interviews is to highlight insights and experiences as told by many of the software testing field’s leading thinkers.

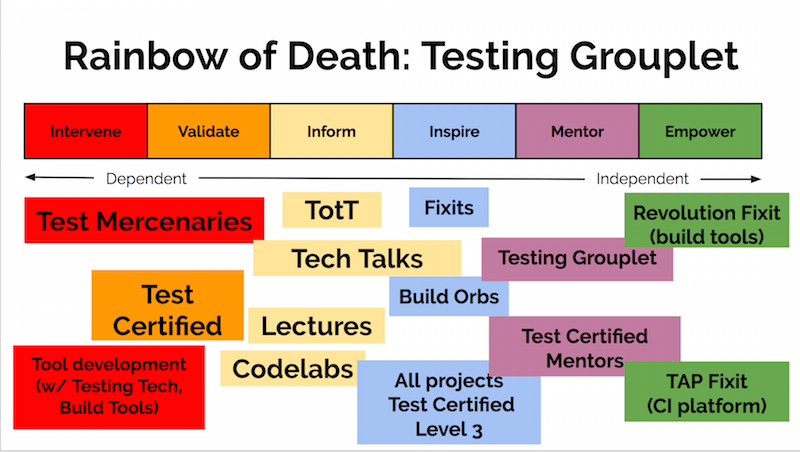

Mike Bland aims to produce a culture of transparency, autonomy, and collaboration, in which “Instigators” are inspired and encouraged to make creative use of existing systems to drive improvement throughout an organization. The ultimate goal of such efforts is to make the right thing the easy thing. He's followed this path since 2005, when he helped drive adoption of automated testing throughout Google as part of the Testing Grouplet, the Test Mercenaries, and the Fixit Grouplet.

Mike Bland

This post includes highlights from our full interview with Mike Bland. The full interview is long and packed with great thoughts.

Personal Background

Hexawise: If you could write a letter and send it back in time to yourself when you were first getting into software testing, what advice would you include in it?

Mike: When I first started practicing automated testing and had a lot of success with it, I couldn’t understand why people on my team wouldn’t adopt it despite its “obvious” benefits. One of the biggest things that experience, reading, and reflection has afforded me is the perspective to realize now that different people adopt change differently, at different rates and for different reasons, and that you’ve got to create the space for everyone to adapt accordingly.

As I say in my most recent presentation, “The Rainbow of Death”, metrics and arguments are far from sufficient to inspire action in either the skeptical or the powerless, and the greater challenge is to create the cultural space necessary for lasting change.

Oh, and you’ve got to repeat yourself and say the same thing different ways multiple times—a lot.

Hexawise: What change management lessons did you learn while driving adoption of test automation methods at Google between 2005-2010? Which of those lessons were applicable when you were involved in the recent U.S. federal government effort to bring in talented tech people to bring new ways of working with technology into the government? Which of those lessons were not?

Mike: The top objective is to make the right thing the easy thing. Once people have the knowledge and power to do the right thing the right way, they won’t require regulation, manipulation, or coercion—doing things any other way will cease to make any sense.

Most of what I learned in terms of specific approaches to supplying the necessary knowledge and power has come from trying different things and seeing what sticks—and I’m still working to make sense of why certain things stuck, years after the fact. The most important insight, as mentioned earlier, is that different people adopt change differently, for different reasons, and as a result of different stimuli. Geoffrey A. Moore’s Crossing the Chasm was the biggest eye-opener in this regard. Then, years later, when I saw fellow ex-Googler Albert Wong present his “Framework for Helping” to describe his first experience in the U.S. Digital Service, I instantly saw it snapping in place across the chasm, describing how the Innovators and Early Adopters from Moore’s model—who I like to call “Instigators”—need to fulfill an array of functions in order to connect with and empower the Early Majority on the other side of the chasm. Of course, through the filter of my own twisted sense of humor, I thought “Rainbow of Death” might make the model stick in people’s brains a little better.

So these models helped provide context for why the specific things the Testing Grouplet did worked; and how, despite the fact that there were many scattered, parallel efforts underway, they ultimately served to reinforce one another, rather than creating confusion and chaos. Of course, Google’s open communication channels and the Testing Grouplet’s shared vision—that emerged two years into our five year run—helped keep everything aligned. The point being, don’t wait for the clear vision and perfect plan up-front—start doing things and pay attention to what’s working, and why, and develop your plans as you go. That’s just good Agile practice, isn’t it?

And did I mention that you have to reiterate things you’ve already said in different language over and over—like, a lot?

Every lesson applied, in that the real lessons were about human nature, not technology. Google disabused me of the notion that one metric, one tool, or one method of persuasion would suffice to change an entire population's behavior. In other words, there's no silver bullet.

See the full interview for useful details.

The top objective is to make the right thing the easy thing. Once people have the knowledge and power to do the right thing the right way, they won’t require regulation, manipulation, or coercion—doing things any other way will cease to make any sense.

Hexawise: Describe a testing experience you are especially proud of. What discovery did you make while testing and how did you share this information so improvements could be made to the software?

Mike: Probably like many folks, I remember my first time the most vividly. Immediately on the heels of a death march—when my team barely got a steaming pile of other people’s code to meet a critical spec by a harsh deadline and very nearly would’ve killed one another were it not for Strongbad’s Emails to keep us one hair’s breadth away from going completely insane—we got some time and freedom to try to make the program faster.

I’d gotten the idea that we needed to rewrite a particular subsystem to take advantage of data we weren’t even using, and at about the same time, I happened to read an issue of the C/C++ Users Journal that had an article on using CppUnitLite, I believe. Unit testing sounded like a neat idea, so I practiced it at the same time I started rewriting this subsystem from scratch.

In the end, my new subsystem was rock-solid and improved performance by a factor of 18x. When a couple bugs came up, I diagnosed and fixed them very, very quickly, when the norm was on the order of weeks or months. It totally transformed our relationship with our client.

See the full interview for additional useful details.

Hexawise: In watching your videos and reading your content online your ideas resonate with those of W. Edwards Deming, Russell Ackoff and Peter Senge from management, culture change and systems thinking perspectives. Who are your greatest influence in this area?

Mike: I’m a little ashamed to admit I haven’t read any of their stuff, or at least not much. Certainly what little I’ve gleaned of Deming resonates with my experience. I’ve begun reading Senge’s The Fifth Discipline, and while the introduction resonated very clearly, I’ve not yet read further. Ackoff is a new name for me (and thanks for the tip!). That said, it is gratifying when I do read an established author and find that, yep, more learned minds than mine have clearly articulated widely-accepted concepts that I’ve only figured out due to trial, error, and intuition.

In fact, one of the things I’m trying to do moving forward is to go back through the literature and connect it to the experiences I’ve had—not just for my own validation, but to reassure my audience and clients that the things I’ve done and the things I recommend aren’t all crazy talk. I’ve got Geoffrey A. Moore’s Crossing the Chasm model combined with Albert Wong’s model to form the Rainbow of Death, which comprises the core of my narrative now; and I’ve also recently added a very high-level view of Kurt Lewin’s theory of social change, which someone only recently suggested to me.

Views on Software Testing

Hexawise: In your online presentation, Making the Right Thing the Easy Thing, you note: [Use] "amplifying feedback loops to make sure knowledge is shared where needed as quickly and clearly as possible." How do you suggest this idea be applied by those involved with software testing?

Mike: Heh, that’s a paraphrase of the Second Way of Devops (out of Three), originally articulated by Gene Kim. Clearly the extent to which you can automate testable cases, to make it easy and fast to do, the better. People need to know that there are different kinds of automated tests for different levels of the software—they need to learn how to do the right thing the right way. Once developers in particular have gotten some traction with writing automated tests, then folks performing manual or system-level automated testing won’t waste their time catching (and re-catching!) bugs the developers could’ve easily caught, and can focus on truly pushing the limits of the software—reporting not just on whether it meets functional and nonfunctional requirements, but on the overall quality of the product.

In other words, a healthy balance of automated testing and manual testing plays to the strengths of all the humans and machines involved. When you’ve got optimal resource utilization happening, you eliminate a lot of both physical (in terms of slowness) and human friction, and a feeling of true partnership can take hold. Testers aren’t just the people reminding you that your code isn’t perfect—you’ve already reminded yourself of that through your own automated tests!—they’re the ones helping you make it even better.

it’s not about defects; it’s about feedback and collaboration. If you arrange incentives to produce an adversarial relationship between team members, e.g. if developers are incentivized to minimize defects and testers are incentivized to report defects, then that’s a house divided against itself.

Hexawise: What do you wish more developers, business analysts, and project managers understood about software testing?

Mike: Oh my. For one, it’s not about defects; it’s about feedback and collaboration. If you arrange incentives to produce an adversarial relationship between team members, e.g. if developers are incentivized to minimize defects and testers are incentivized to report defects, then that’s a house divided against itself. Some people think a degree of competition and/or adversarialism is a good thing, but when it comes to producing a product as a team—i.e. achieving a mission—you should keep it to a minimum in favor of fostering a spirit of collaboration.

Collaboration doesn’t mean blind consensus; it means communicating honestly in an environment in which we feel safe to do so, in which we share criticism in a spirit of mutual self-interest, not cutthroat competition.

One test type does not fit all. First, in terms of automated tests, unit testing can find a truly large number of errors, very quickly and cheaply, and tends to encourage better code quality (i.e. readability, maintainability, extensibility) overall. Integration tests can shake out errors and ambiguities between component contracts. High-level, developer-written system tests (as opposed to more extensive system tests developed by a dedicated tester) can quickly affirm that the entire product is in a buildable, runnable state. All of this “white box” testing by the developers is essential to giving the testers as high-quality a product as possible, so they can apply their “black box” techniques to push the product to its limits, rather than waste time alerting developers to defects they could’ve much more quickly, easily, and cheaply discovered themselves.

To this last point, I like to point to the examples of goto fail and Heartbleed. So many Internet “experts” threw up their hands and claimed that bugs like these were “too hard to test”. In both cases, after 2.5 years out of the industry (another story), I spent an evening diving into code I’d never seen before and wrote a test to reproduce each bug and validate its fix. After that, some liked to say, “Oh well, lots of other tools and techniques could’ve found these bugs.”

My claim isn’t that automated testing would’ve been the only way; my claim is that the discipline of automated testing likely would’ve prevented these bugs from ever existing even before writing a single test. With goto fail, the offending block of code was copied and pasted throughout the file six times! It was just that one of the six contained the errant “goto fail” line. But as I demonstrated with my version of the “fix”, extracting a common function and testing that six ways from Sunday likely would’ve avoided the problem entirely. In the case of Heartbleed, it was a failure to validate that an input buffer was actually as long as the user-supplied length indicated. Testing that kind of corner condition is unit testing 101, and the kind of thing you become more sensitive to every time you write a line of code once you’re in the habit of testing.

Hence, as difficult as it would’ve been for manual testing to discover these errors, and as long as it took for them to get shaken out months or years after their widespread deployment—Heartbleed via third-party fuzz testing, goto fail who knows how—both very, very likely could’ve been stopped dead in their tracks (or never would’ve existed!) if the developers were in the everyday habit of unit testing their code.

Hexawise: Our CTO, Sean Johnson, shared your memorably-named "Rainbow of Death" presentation with our management team. We absolutely loved it. In your presentation, you describe a series of concrete, practical steps you and your colleagues at Google took over the course of 5+ years to overcome resistance to change, educate teams, and successfully achieve broad adoption of automated testing efforts at Google across many teams, including lots of teams that were initially very change resistant. Can you please describe for our readers 2 or 3 noteworthy aspects of that change management journey?

Mike: What I hope the Rainbow of Death model, in combination with Geoffrey A. Moore’s Crossing the Chasm model, make apparent is that different people adopt change differently. There are many needs that need to be met by and for many different people, and the chances of figuring out the perfect plan to execute before taking any action are practically zero. After all, don’t the Agile and DevOps models that are all the rage comprise tools and practices for adapting to change, for performing experiments and adjusting course based on feedback? Organizational change is no different, yet many people remain conditioned to expect waterfall-like solutions to their social problems.

Also, I mention in the talk that “The problem you want to solve may not be the problem you have to solve first.” In our case, we wanted to solve the problem of developers not writing enough automated tests. But first, we had to solve two other problems: People back then had very little exposure to or experience with automated testing, leading to the “My code is too hard to test” excuse, because they had no idea how to test it, or to write testable code to begin with.

The second problem was that the tools at the time couldn’t keep up with the growth of the company, its products, and its code base. It was growing ever more painful to write any code to begin with, yet delivery pressure was intense and Imposter Syndrome was rampant—on top of the fear of admitting your code might contain flaws, how could you make any time to learn how to write automated tests to begin with? Hence the “I don’t have time to test” excuse.

So we couldn’t just say “Testing is good! Yay testing! Please write moar testz!”

I think this mix of perspective, empathy, creativity, collaboration, tenacity, and patience is crucial to changing not only tech organizations, but society at large. I hope to put this notion, and the Rainbow of Death model in particular, to the test continuously throughout the remainder of my career.

my advice to both developers and testers is to identify the priorities, the social structures and dynamics at play in the organization. How can you work with these structures and dynamics instead of against them—or do you need to create a culture of open communication and collaboration in parallel with (or even before) communicating the testing message?

Industry Observations / Industry Trends

Hexawise: Large companies often discount the importance of software testing. What advice do you have for software testers to help their organizations understand the importance of expecting more from the software testing efforts in the organization?

Mike: Sadly, there’s no one message that works for every company, every culture, everywhere. It’s up to the Instigators in each environment to take the timeless principles I believe are essential—that testing is about feedback and collaboration, that different types of tests all catch different and important bugs, that developers and testers have different and mutually-reinforcing roles to play—and find the right cultural hooks to hang those messages on. In the case of Google, it took the Testing Grouplet five years to figure out and successfully implement, and it took an array of parallel efforts across multiple groups to saturate the culture with the message, not just one magical tool or technique or team to bind them all.

So my advice to both developers and testers is to identify the priorities, the social structures and dynamics at play in the organization. How can you work with these structures and dynamics instead of against them—or do you need to create a culture of open communication and collaboration in parallel with (or even before) communicating the testing message? This is the punchline of my Rainbow of Death presentation: The problem you want to solve may not be the problem you have to solve first, and the Standard Narrative from which all the problems emerged will not produce any solutions—though it may provide the keys necessary to unlock effective solutions.

At Google, it was the Testing Grouplet’s Test Certified program and all the other education and tooling efforts supporting it that provided the right hook—after two years of experimentation and reflection! But don’t focus on what Test Certified was comprised of: focus on why that approach worked for us, and see if that reflection inspires an approach that will work for your company.

In addition to that, it probably wouldn’t hurt to remind anyone who’ll listen of goto fail and Heartbleed, and how basic unit testing practices and the coding habits they encourage could’ve prevented these potentially catastrophic defects from even being written in the first place.

Hexawise: The story of your team's journey is fantastic. We highly recommend it to IT organizations embarking on any large improvement effort. Thank you for sharing it. We've recently started using elements of your approach to help our clients successfully adopt test optimization approaches at scale in their organizations.

Mike: That’s incredibly gratifying to hear! Please keep me in the loop of how well it’s working for you and your clients. Just as the impact of Testing Grouplet’s efforts were far greater than the sum of any individual part, and as my Rainbow of Death presentation benefited enormously from the input of trusted fellow Instigators to help illustrate it, I’m sure there are many more insights and improvements waiting to emerge from the model once more people have applied it farther and wider than I ever could on my own!

Hexawise: Do you believe the DevOps movement is resulting in better software testing within organizations? Do you see any other trends that software testers could leverage to promote improved application of software testing practices?

See full interview for Mike’s response.

Staying Current / Learning

Hexawise: What software testing-related books would you recommend should be on a tester’s bookshelf?

Mike: Sadly, I’m not current enough to make any solid recommendations. In my career, I’ve moved more into the culture change space than being a 100% in-the-trenches practitioner. That said, I certainly did years of quality time with my old “library” of programming and algorithms books, and was fortunate to be part of a culture that itself generated a broad swath of automated testing knowledge. Though I don’t keep up with the details of the latest developments, that time spent internalizing the core principles has served me very well throughout my career.

That said, I’m sure that great books exist, and people dedicated to the craft would do themselves a great service by discovering them and spending years plumbing their depths, rather than trying to read every book on the subject forevermore. That’s the model that worked for me, at least; but perhaps a more voracious reading regimen suits you better. Everybody’s different.

See the full interview for more questions and answers.

Profile

Mike aims to produce a culture of transparency, autonomy, and collaboration, in which “Instigators” are inspired and encouraged to make creative use of existing systems to drive improvement throughout an organization. The ultimate goal of such efforts is to make the right thing the easy thing. He's followed this path since 2005, when he helped drive adoption of automated testing throughout Google as part of the Testing Grouplet, the Test Mercenaries, and the Fixit Grouplet. He was instrumental in the execution of Test Certified and Testing on the Toilet, and the four company-wide Fixits he organized led to the development and rollout of the Test Automation Platform. His account of Google’s automated testing adoption also appears as a case study in The DevOps Handbook by Gene Kim, et. al.

He also served as a member of the Websearch Infrastructure team, which practiced DevOps before he was aware it had a name. Frequently working in concert with other indexing infrastructure teams, he also worked closely with Release Engineers and Site Reliability Engineers to package, release, deploy, and monitor multiple indexing services.

Most recently he served as Practice Director at 18F, a technology team within the U.S. General Services Administration, where he personally launched and drove several initiatives to increase 18F’s capability as a learning organization, including the Pages platform, the Guides series, and the Handbook.

Links:

This post includes highlights from our full interview with Mike Bland. The full interview is long and packed with great thoughts.